It can be mesmerizing watching concert pianists as they play piano concertos or masterpieces from Bach and Beethoven. It’s hard to think that those professionals started with simple skills like learning notes, scales, and hand placement. Now they are at the elite level; it could well leave you curious to wonder whether they still need to practice their scales?

Professional pianists may practice scales to hone their skills throughout their careers. However, they would have been an underlying part of their early practice sessions. Scales are fundamental to learning to play any instrument; they help develop speed and awareness of the notes and are a great warm-up.

Even though concert pianists have proven to be successful with their instruments, there’s an immense complexity to the variety and different types of scales. Keep reading to dive into the different kinds of scales, their significance, and why practicing them is so important.

What Are Scales?

If you’ve ever studied music theory, you likely already know that the idea behind different scales can be incredibly complex and serves an essential role in creating a piece of music.

A scale consists of notes arranged by their pitch to produce melodies and harmonies. The word scale derives from the Latin word “scala,” which means ladder. Think of a scale as a ladder of notes arranged in different groups.

Each scale represents different musical degrees. Each degree has a specific identifier, such as:

- 1st degree: tonic

- 2nd degree: supertonic

- 3rd degree: mediant

- 4th degree: subdominant

- 5th degree: dominant

- 6th degree: submediant

- 7th degree: leading note

Depending on the type of scale, these degrees’ order will differ, as each type arranges the tones in a particular order. Tones (whole steps) and semitones (half steps) are used to define the pattern of the scale according to the tonic.

The Importance of Scales

Not only do scales quite literally make up the notes and patterns of every single song, but they also serve as the foundation to building groups of notes called “chords” in music. Scales allow you to set the mood for the piece of music and pull the listener in through your expression. They create a sense of fluidity throughout the music and are pleasant.

Scales categorize sets of tones to allow songwriters and musicians to be intentional when composing their music.

Why Practicing Scales is Important

Scales are an essential part of any instrument’s practice time, and every piano teacher worth their salt will focus and encourage their students to practice them along with arpeggios.

They are technical exercises that teach you how to quickly move your fingers over the keys with control and help develop finger strength and muscle memory. This leads to improved agility and accuracy in your fingers, two crucial skills needed for any instrument player!

Scales can also be used as part of a deliberate practice routine as you can set goals and measure your progress. For example, you could set the tempo to 60bpm and keep time, first with one hand, then the other, and then together. Once you’ve mastered this, it’s time to increase the tempo or change to a more challenging key.

Another benefit of playing scales is that it helps develop your musical ear. It sounds very different when you play a scale from when you “play notes.” This is because scales are based on specific intervals that sound nice together and help compose the harmony of music.

Although concert pianists and those at the top of their game don’t incorporate scale practice into their daily routine once they’ve achieved piano mastery, you can bet that a considerable amount of practice time was dedicated to it on a daily basis as they learned their craft.

Main Types of Scales

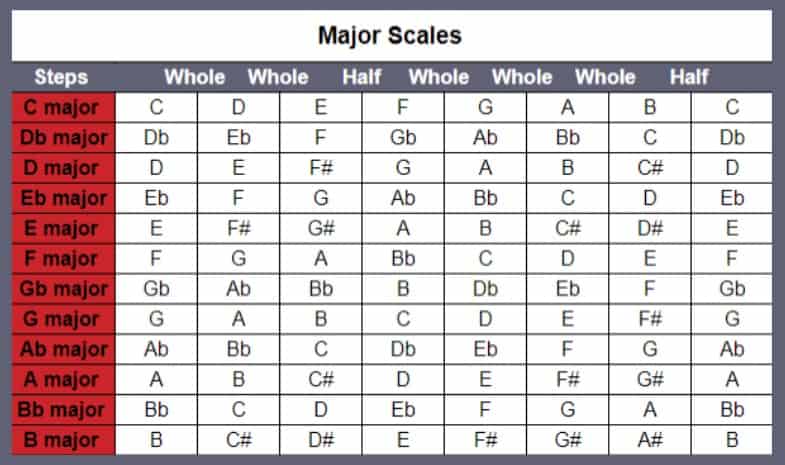

A professional pianist with over 15 years of teaching experience, Joshua Ross notes that over 48 musical scales are typically used in compositions. Those 48 scales consist of 7 steps taking the original root and ascending an octave higher. These come in both major and minor forms.

Major scales follow the same formula no matter which of the 12 keys are being played. It starts to get a little complicated when it comes to minor keys as there are three types to consider – natural, harmonic, and melodic.

Major Scales

Major scales are defined as a diatonic scale, that is, a scale with seven different notes. Each major scale follows the same formula regarding the tones.

Start with the root note, and travel up the ladder with the following seven steps until you reach the root note an octave higher:

- Whole (Tone)

- Whole (Tone)

- Half (Semitone)

- Whole (Tone)

- Whole (Tone)

- Whole (Tone)

- Half (Semitone)

This formula will create any major scale for the selected root note. Within the 12 major scales, seven of them start on white piano keys, while the other five begin on a black key.

The 12 major scales, including the starting keys, are:

| White Key Start | Black Key Start |

| C major | Bb major |

| G major | Eb major |

| D major | Db/C# major |

| A major | Ab/G# major |

| E major | Gb/F# major |

| F major | |

| B major |

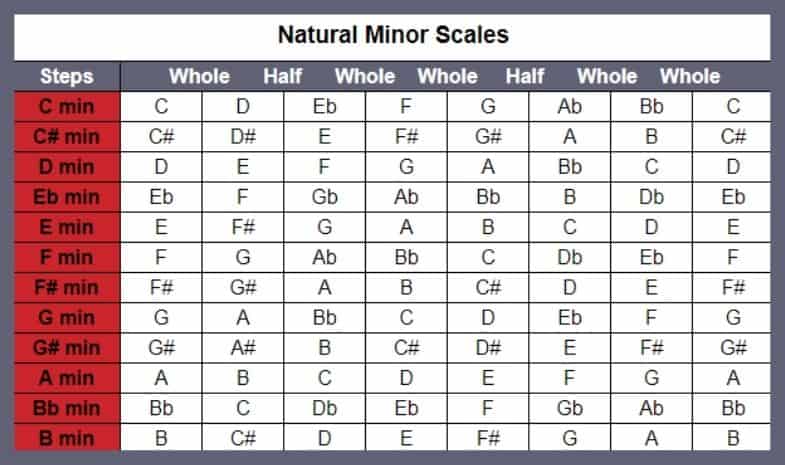

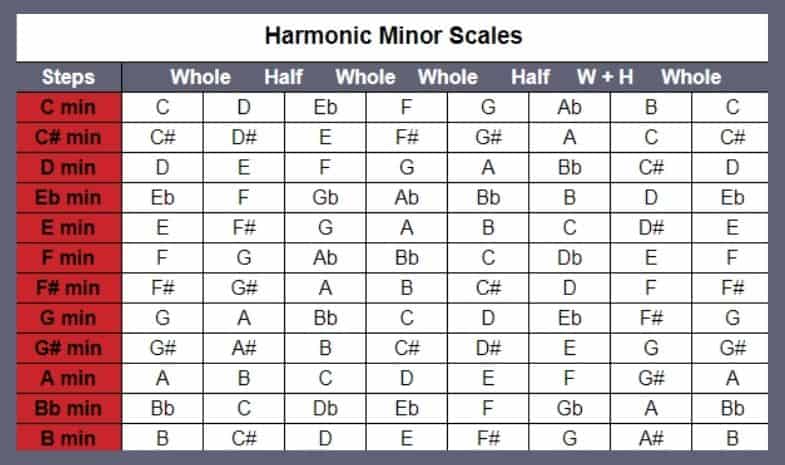

Minor Scales

While there is only one formula to produce a major scale, minor scales have three variations: natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor. Minor scales can depict a more somber tone, and selecting the desired variation can help compose the perfect melody.

Both harmonic and natural minor scales involve shifting one to two notes within the natural scale. The harmonic minor follows the same first six notes as the natural minor but adds an extra half (semitone) step to reach the seventh note.

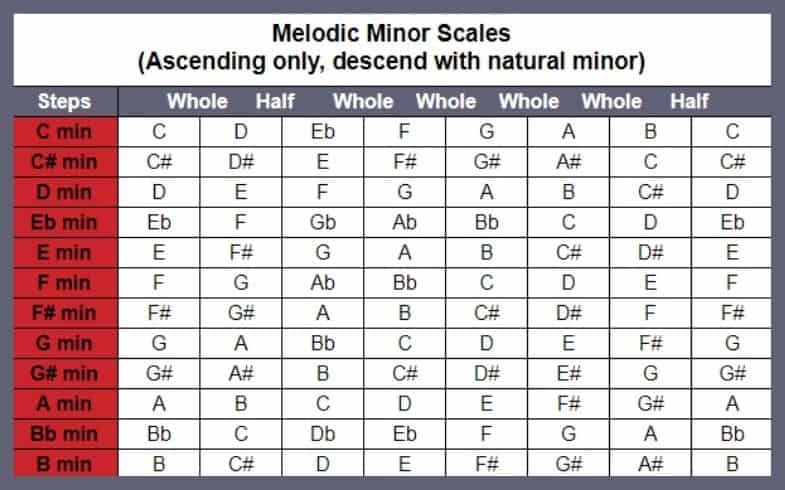

The melodic minor is a bit more complicated as it plays slightly different notes on the way up as it does coming back down. Or the ascending it adds an extra semitone to step 5 and reduces a semitone on step 7. Coming back is easier as it follows the natural minor path.

These three variations utilize the following formulas:

- Natural minor: Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole

- Harmonic minor: Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Half, Whole + Half, Half

- Melodic minor: Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Whole, Whole, Half

More Scales, Arpeggios, and Fifths

The above scales cover the basic 48 types; however, it doesn’t end there. There are also others, including the chromatic, whole tone, and pentatonic. In addition to scales, composers and songwriters will utilize the circle of fifths when creating music. The circle of fifths involves the notes within the scale.

Chromatic Scale

The chromatic scale uses all 12 notes throughout its intervals. Each interval is a semitone from the previous tone. That is, if you start on one note, you’ll continue working your way up the rest of the scale with half steps until you reach that same note again one octave higher.

Whole Tone Scale

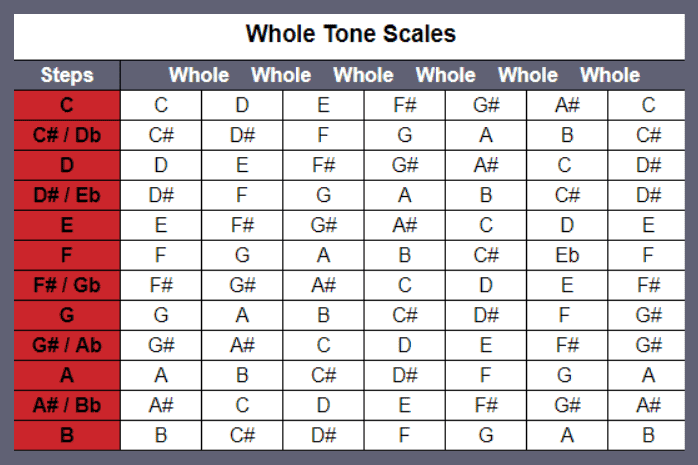

Where the chromatic scale uses all 12 notes and semitones between each note, the whole tone scale is opposite and utilizes notes that are a whole step. This scale comprises six notes to complete the whole tone scale. Since there are only six notes, this is classified as a hexatonic scale.

Pentatonic Scale

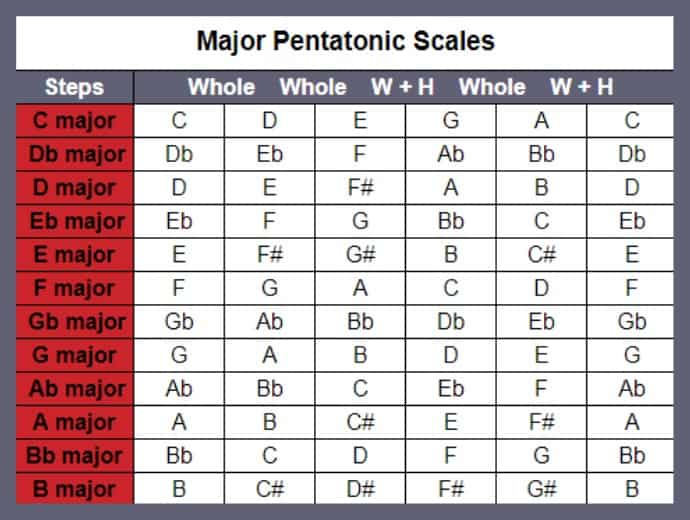

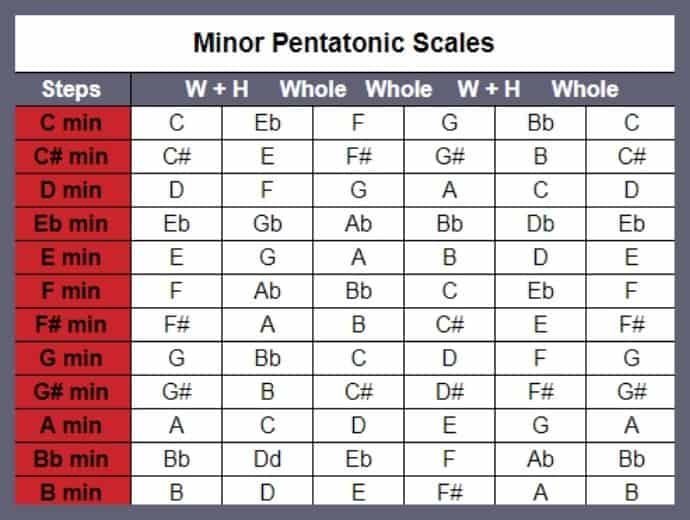

The pentatonic scale is another set of scales that come in major and minor varieties, this time consisting of 5 notes to reach the octave root.

Again they both have their unique formulas:

Major: Whole, Whole, Whole + Half, Whole, Whole + Half

Minor: Whole + Half, Whole, Whole, Whole + Half, Whole

The pentatonic scale is very common and is used in a wide range of music and is known for its simplicity.

Arpeggios

Arpeggios and chords go hand in hand. While chords are made up of different notes within a scale simultaneously, an arpeggio would simply be playing each of those notes in the chord individually. Using arpeggios throughout compositions and songs allows the instrumentalist to glide through the music.

If a song consists mainly of chords, playing notes on an individual basis can allow you to string chords together and create seamless transitions.

Circle of Fifths

While we’ve previously spoken about the chromatic scale, an important aspect to note is the notorious circle of fifths. The circle of fifths is a circle that shows the relationship between the 12 tones on a chromatic scale.

This is typically a diagram depicting the relationship between major and minor keys’ key signatures. It’s called the circle of fifths because as the circle’s structure goes clockwise, the following note will be the natural 5th (7 semi-tones) of that scale. G is the fifth in C major, D is the fifth in G major, etc.

The key signatures also change incrementally as you descend to the bottom of the circle, going both clockwise and anti-clockwise. i.e., Cmaj/Amin has zero sharps & flats, whereas Gmaj/Emin has 1 sharp, etc.

This formula also works for the minor keys displayed in the inner circle.

How To Memorize Piano Scales

Piano scales are a powerful tool for writing music, but it won’t be easy to utilize them if you don’t have them memorized. The easiest way to remember piano scales is to use the formulas unique to the specific scale. If you can learn the formula, you can start with any desired note and apply it to create the scale.

You can also invest in a music theory practice book with ample information to learn and memorize piano scales. The Piano Book for Adult Beginners by Damon Ferrante and The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences by Willard A. Palmer, Morton Manus, and Amanda Vick Lethco are excellent supplemental education resources.

Final Thoughts

No matter what level you are at, practicing scales is essential for your piano playing journey. However, they require practice and effort to achieve fluidity and practical application.

Professional pianists will still use them for effective warm-up routines, and they constantly provide opportunities for them to perfect their craft.

At first glance, it may seem daunting, but while scales are a complex music component, you can navigate them by memorizing formulas and practicing.

Without scales, music would be a jumbled mess of tones and semitones in no particular order or design. Scales allow us to interact with the varying moods and feelings that come from music.